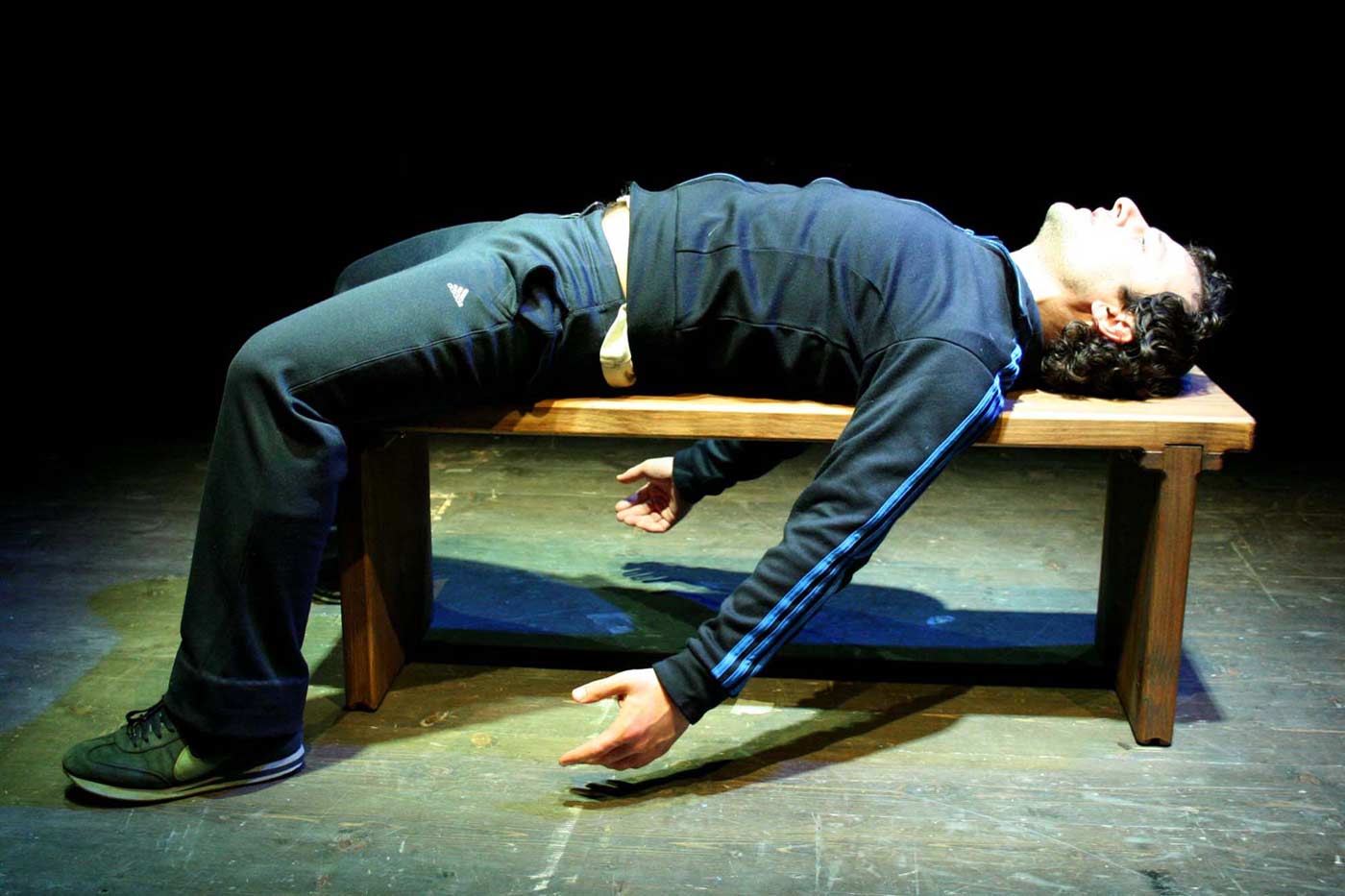

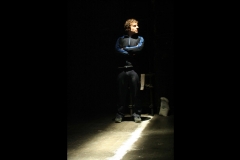

On tiptoe

dramaturgy and direction Francesca Macrì and Andrea Trapani

with Andrea Trapani

stage lighting designer Mirco Maria Coletti

production year 2006

So, Pasolini, what is it that hypnotises you in football?

“Football is the last holy representation of our time. It is a ritual at the end, even if it is an escape. While other holy representations, even the Mass, are in decline, football is the only one left. Football is the show that replaced the theatre. Cinema could not replace it, football did. Because theatre is the relationship between audience in person and characters in person who act on the stage. While cinema is a relationship between an audience in person and a screen, shadows. Instead, football is a show in which a real world in person, sitting on the stadium stands, challenge itself with real protagonists, the athletes on the football field, who move and behave according to a specific ritual. So I consider football the only great ritual left in our time. ”

Guido Gerosa interviews P.P. Pasolini, “L’Europeo”, 31 December 1970

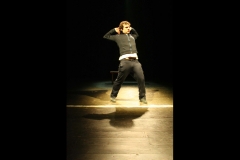

Florence, adolescence and football.

On tiptoe was conceived from the intertwining of these three topics and the persistent scents of the 1980s, still too close to look at them like an old picture but far away enough to feel the ferocity of memory under the skin.

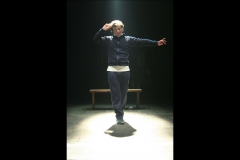

A teenager and his city, beautiful with a rare beauty, but resistant to play and naturally slave to competition. Florence that likes being looked at, but never re-looks, if it could, would hit from behind anyone who would like to possess it.

A teenager and the obsession of a generation, a century-long fanaticism: the game of football.

In Pasolini’s words you can and must feel the strength of a symbol, such as that of football, able to connect thousands of bodies in only one soul. In this long twentieth century a few other realities have been able to go so deeply into rituals.

Football has won. He over-won. But with over the years, something in this ritual broke, the power of televisions and the mass media disfigured its authenticity and the eighties immortalized the final parable of a ritualized football that was about to be delivered to the light blinding of media spectacle. Nothing would ever be the same again.

These are the years of Mastino, the protagonist of this monologue: the years of man marking, of hand-to-hand matches, of the numbers on the shirts, staring at specific roles.

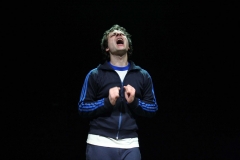

It’s an ordinary Sunday morning, in a football field of the Tuscan suburbs, where the grass never grows. Mastino would like to play, but the coach relegates him, as always, to the role of benchwarmer. He’s a low quality player and in several occasions he’s pointed out about his inability to play football, but as often happens at eighteen, certain truths are quite hard to understand and, even more, to accept. At eighteen years, being out of football can often mean being out of the loop, the right one, which makes you feel part of a whole, as at school just as when you walk through the neighbourhoods of the city.

Sitting on the bench, Mastino lives, as an excluded, the agony of another, very long Sunday.

He watches the game, talks to the coach, talks about himself and his eternal rival, that number 11 on the football field as in life: Golgòl, nicknamed for his habit of following the ball once he has entered the net, to emphasise that his foot made the right move. This young playmaker is the symbol of all Mastino’s suffering, because he’s all that he can’t be.

Sitting on this prison-bench, Mastino looks at him, he admires and hates him.

Minutes pass in the same way any given Sunday until the coming of a girl which alters the habit, encouraging Mastino to disobey the coach, in order to get in the game and play his game once for all. Maybe the last one.